Sri Lanka is approaching its 73rd year, post-independence from its colonial masters, ‘The British Empire’. It is unfortunately still struggling to make use of the one advantage, a non-depleting natural resource; ‘geographical location’. The location provides a natural focal point for shipping and airline operations generally known as a ‘logistics hub’.

Let us elaborate on the actual potential: Sri Lanka is part of three sub-regional organisations. They are SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation – Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Maldives, Bangladesh), BIMSTEC (Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectorial Technical and Economic Cooperation – Bangladesh, India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Bhutan and Nepal), and IORA (Indian Ocean Rim Association – Australia, Bangladesh, Comoros, India, Indonesia, Seychelles, Iran, Somalia, Kenya, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mauritius, Mozambique, Oman, Singapore, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Thailand, United Arab Emirates, Yemen); which means that Sri Lanka has entered into some form of trade, investment and technical corporation with 27 countries in our immediate neighbourhood (in and around the Indian Ocean).

We are surrounded by 27 countries which have 158 international airports and 196 ports. These 27 countries had a GDP (Nominal) of over $ 6 trillion (based on IMF data) in 2018. The “Hub” opportunity we have is, to channel the trade and investment i.e., the movement of goods and service, people and capital not only to and from Sri Lanka, but also to those countries in the periphery of Sri Lanka, routed through Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka was perhaps creeping its way to being such a location when the pandemic struck.

No political party or its leadership, current or in the past can take credit for exploiting this to its full potential thus far. However, all political parties and their leadership since independence, are responsible for the failure to fully understand this potential and to take full advantage of it for the benefit of its citizenry. A clear lack of vision within the global and regional context, engaging in petty party survival politics intertwined with periodic politicisation of race and religion, has led to a situation that repeatedly elected leadership of this country not having cognisance of this opportunity.

In fact, a key to taking advantage of this opportunity is to develop appropriate infrastructure, have policies, procedures and rules that enable a hub operation. Have people trained in the skills needed for a hub operation and most importantly deploying other peripheral resources to support the hub function. This country’s strategy must happen irrespective of which political party and who gets elected as our leaders. It is a sad reflection that Sri Lanka has come up short at every turn up to now. The irony is that most citizens are content to wait for it to happen and are willing to wait longer and longer for it to happen.

At the end of the war in 2009 we all waited in anticipation to become the so-called, ‘Hong Kong’ of India. I suppose we are still waiting for this to happen. This kind of change will not happen by chance; it has to be designed and built from scratch by Sri Lanka. Unlike with Hong Kong and China, India has no interest in allowing or supporting Sri Lanka to become the ‘Hong Kong’ of India. They rather have their own hub operation at the tip of South India. Unlike Sri Lanka, India is moving very fast on doing just that.

In my book titled “How small countries can compete and grow – A case for Sri Lanka”, I argue the need for the development of the Trincomalee Port as the eastern terminal of Sri Lanka, where all Bay of Bengal ports (east coast of India, Bangladesh and Myanmar) bound FCL and LCL cargo be directly transferred from the ships (docking at Colombo port) to Trincomalee Port using a high speed dedicated bonded freight line. This transfer could be done in about one hour. This will allow all feeder lines to avoid the need to make the slow circuitous journey around Sri Lanka to call over at the Colombo Port. This move also has the added advantage of opening up space within the Colombo port thereby allowing it to increase its throughput of TEUs.

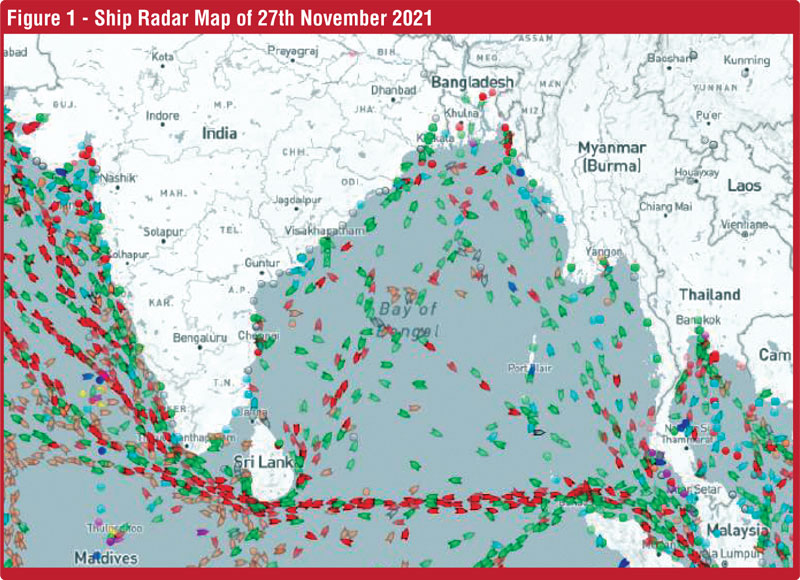

As shown in Figure 1, at present Chennai Port has more ship calls than Trincomalee Port; from the radar picture you can see a convergence of ships toward Chennai port. The same can’t be said about Trincomalee Port; you can see ships still converging to go around Sri Lanka and heading toward Singapore.

Enter India at 74; India is developing its own competing infrastructure as mentioned in my book; India is developing the deep water “Vizhinjam International Seaport” in the west coast of southern India, in the State of Kerala and an all-weather deep water “Karikal Port” in east coast of southern India in the State of Tamil Nadu. In fact, these port builders and operators are already in consultation with these large vessel owners to ensure their patronage of these ports once operational. In addition to this India is developing Pondicherry Port and Chennai Port (one of the 12 major ports of India) which is just one hour flying time (as shown in Figure 2) and four hours by road from Vizhinjam Seaport.

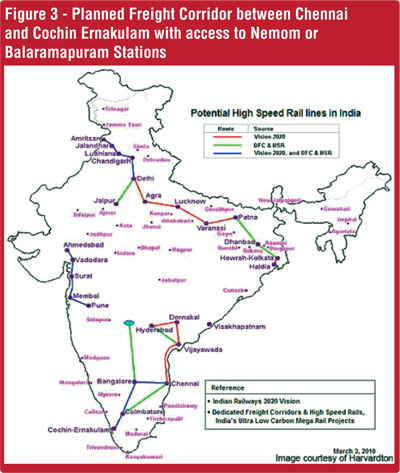

Coupled with another successful strategy, India has been able to implement “freight corridors” as shown in Figure 4. Plans are underfoot to link the two ports with a freight corridor (as shown in Figure 3). Vizhinjam Seaport is just 20 minutes away from Nemom or Balaramapuram Railway Stations. It is reasonable to assume that India will build the rail access right into the Vizhinjam Seaport. This means that a high-speed rail line will link these ports. The implications for Sri Lanka are potentially catastrophic.

Firstly, India is going to be a massive economy and it is well on its way to becoming that. The only debate is whether it will be the 3rd or 4th largest economy behind China and the USA. Once it achieves this position it will have enormous influence on its neighbouring countries (Bangladesh and Myanmar) as well as corporations operating within India and outside.

Secondly, the pre pandemic freight status between India and Sri Lanka was that, the Colombo port was (and still is) the largest transshipment hub for container traffic to and from India with a share of about 47% (the main reason why the government of Sri Lanka did not close down the port during the pandemic). With the perception that Colombo is more aligned towards Beijing, it is seen as a major risk to the Indian economy.

Once these ports and freight corridors come on line, all feeder lines owned and operated by Indian companies plying routes originating from the east coast of India will switch their final port of call from Colombo to Chennai. India can and will influence Bangladesh and Myanmar feeder line operators to do the same. Therefore, a freight container that is unloaded in Chennai Port can reach Vizhinjam Seaport in around two hours and get loaded to an east/west bound mega container ship much faster and cheaper than being shipped to Colombo.

The same will apply for any and all imports into this region. The increase in the freight volumes due to the growth of India and the routing of cargo to Chennai from two more growing economies (that are several times larger than Sri Lanka) will make it more lucrative for the top 20% of major shipping lines to call over at Vizhinjam Seaport instead of Colombo.

Sri Lanka can however develop its own freight corridor between Colombo Port and Trincomalee Port and offer the same to Indian, Bangladeshi and Myanmar feeder lines. Sri Lanka needs to do this as a priority. Failing to counter this potential move by India will bring Sri Lanka closer to an economic disaster that will have an extremely negative impact.

Indian freight corridor rail in operation